We need to talk about Cyprus

TetleysTLDR: The Summary

Cyprus has always been caught between empires, from the Ottomans to the British and, since 1974, Turkey’s occupation of the north. Britain still controls two sovereign bases, and now Cypriots fear a new ‘soft colonisation’ in the south as Israelis buy thousands of properties in Larnaca, Limassol, and Paphos.

For Israelis, it’s second homes or a hedge against instability. For Cypriots, whose history is scarred by partition, dispossession, and foreign control, it looks like déjà vu. Biblical rhetoric and Zionist pre-history, Herzl once floated Cyprus as a Jewish homeland, only heighten anxiety.

Cypriot leaders like AKEL’s Stefanos Stefanou warn of a ‘silent occupation’, echoing fears that what happened in the north could happen again, this time with money instead of tanks. The question remains the same: when will the island finally belong to its people?

TetleysTLDR: The Article

Cyprus has always been more than an island. Rising from the eastern Mediterranean like a hinge between continents, it has been a meeting point of empires and a crucible of cultures for millennia. The myths tell us Aphrodite was born from its seas; the archaeologists remind us that some of Europe’s earliest farming settlements took root here at a time when the North Sea didn’t even exist and Britain was still connected to Europe. Phoenicians, Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Greeks and Romans all left their mark. Byzantines, Crusaders, Venetians and Ottomans followed, each layering their own architecture, language and faith onto its soil. Cyprus is not just a place on the map, it is a founding pillar of Mediterranean civilisation, a crossroads where history has always been written by the strong and endured by the small.

So it is a sad sidenote of history that Cyprus has never has truly belonged to the Cypriots. The eastern Mediterranean island has always been too strategic, too coveted, and too vulnerable to be left alone. Today, the Republic of Cyprus finds itself in the strange position of being simultaneously occupied, colonised, and increasingly commodified.

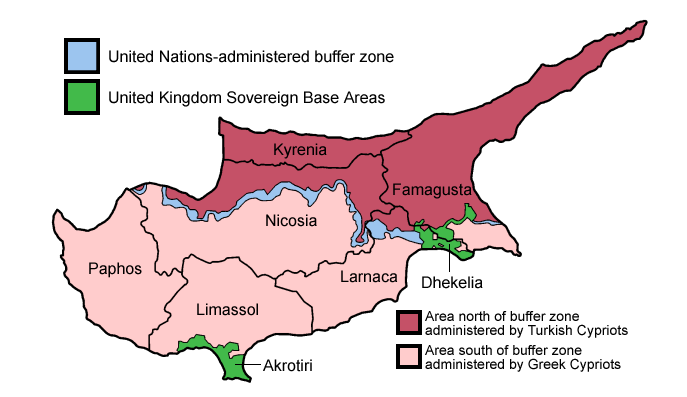

To the north lies the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), recognised only by Ankara, born of invasion in 1974 and cemented through demographic engineering. In the centre and south lie two vast British sovereign bases, Akrotiri and Dhekelia, relics of colonial rule and still vital to NATO strategy in the Middle East. And now, in the Greek-controlled south, Cypriots are raising the alarm over what they see as a new form of encroachment: thousands of Israelis buying up property, building gated communities, and talking about Cyprus as a promised land.

On an island where sovereignty has always been precarious, the fear is simple: what happened in the north could happen again, this time not by force of arms, but through the power of money.

Cyprus was formally annexed by Britain in 1914 (though under British administration since 1878). London ran Cyprus as a colonial outpost until 1960 independence, leaving behind a constitution designed to keep Greek and Turkish Cypriots divided. Many Cypriots still see Britain as the author of partition, having played Greece and Turkey off against each other to maintain control. Sounds familiar?

So when Cypriots today look at new foreign interests buying land, they remember the old imperial pattern: outsiders using Cyprus as a pawn.

During the 1950s anti-colonial struggle (EOKA), Britain leaned on Turkey to counterbalance Greek Cypriot demands for Enosis (union with Greece). When Turkey invaded in 1974, Britain as one of Cyprus’s guarantor powers under the independence treaty stood aside and did not intervene. Many Cypriots believe London tacitly allowed partition to cement NATO’s hold on the island. This deepened distrust: Britain seen as the architect, Turkey as the enforcer.

Under the 1960 independence agreements, London retained two ‘Sovereign Base Areas’ at Akrotiri (near Limassol) and Dhekelia (near Larnaca/Famagusta). These are fully under British sovereignty, covering about 3% of the island, military enclaves, not just bases. Akrotiri in particular is crucial for UK and NATO operations in the Middle East. It was used in Iraq, Syria, Libya, and is currently a key staging ground for RAF flights over the Red Sea and eastern Med. Most recently staging points for British questionable intervention the Gaza conflict. For Cypriots, that’s another form of permanent foreign ‘settlement’ on their soil.

Since 2021, Israeli citizens have been acquiring real estate in southern Cyprus at an unprecedented rate. Estimates put the number of properties bought by Israeli-linked buyers at nearly 4,000, concentrated in Larnaca, Limassol and Paphos, areas that are not just tourist hubs but also strategically significant, close to ports, airports and, in some cases, military installations lemkininstitute.com.

Israeli Property Purchases and Migration Trends

- Non-official migration and investment: Since 2021, Israelis, particularly affluent individuals have increasingly bought property across southern Cyprus. This has been motivated by factors like pandemic-era relocation, political unrest (e.g., judicial reform crisis), and security concerns amid ongoing regional conflicts Lemkin Institute Great Reporter.

- Data indicates nearly 4,000 properties have been acquired by Israeli-linked buyersmany located in gated communities near strategic areas like Larnaca, Limassol, and Paphos Lemkin Institute.

The reasons are varied. Some are wealthy Israelis seeking second homes in a nearby EU member state. Others are families unnerved by Israel’s political instability, especially during the judicial reform crisis. A third group are investors lured by Cyprus’s ‘golden visa’ schemes, property markets and tax regimes. The pandemic also accelerated the trend: many discovered that remote work allowed them to relocate.

It should be said that there's no official Israeli government policy or plan to colonize or establish a formal settlement project in Cyprus akin to what exists in the West Bank or East Jerusalem. That idea remains speculative or based on misinterpretations of certain events and discussions. However, some ultranationalist and religious-extremist voices, the same voices that in the West Bank have the ear of the Israeli Government have invoked Cyprus in recent years. On TikTok and other social media platforms, claims of Cyprus as a Jewish State of Kittimya and videos have appeared of Israelis claiming a biblical entitlement to Cyprus, declaring things like: “Cyprus was promised to us 3,500 years ago... finally, I’m home” ynetnews.com.

These claims often cite the biblical Eretz Israel: the concept of a ‘Promised Land’ stretching beyond today’s Israel into surrounding regions, sometimes including parts of Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and, in some messianic interpretations, even Cyprus. Such rhetoric has fuelled Cypriot fears that the current wave of property acquisitions could morph into something more ideological than financial.

Cypriots are anxious about this as it falls squarely into the pattern of their history which has been littered with colonisation and conquest. Cyprus has always lived in the shadow of other people’s ambitions. Its strategic location at the hinge of Europe, Asia and the Middle East has made it the pawn of empires, a staging post for invasions, and a listening post for foreign powers. For Cypriots, sovereignty has always been fragile, and the current alarm over Israeli property buying in the south of the island can only be understood in the context of Turkish occupation in the north and Britain’s colonial legacy.

So for Israelis, buying a villa in Limassol may be no more than a hedge against instability at home. For Cypriots, it looks like the beginning of yet another foreign encroachment. In a land where sovereignty has been compromised too many times, anxiety about ‘settlements in all but name’, is not difficult to understand.

This therefore needs to be understood in the context of the founders of Zionism. Despite Israeli claims that Palestine is their promised land, the original Zionists didn’t exactly share this view. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Theodor Herzl and other early Zionists considered Cyprus (along with Uganda, Argentina and Sinai) as a potential site for a Jewish homeland before Palestine became the central project. In 1902 Herzl proposed Cyprus as a refuge for Jews fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe. The idea was floated to the British government but never advanced, largely because Cyprus itself was still a contested territory between Britain, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire (ynetnews.com).

The scheme was eventually abandoned in favour of Palestine, but the episode remains part of Zionist pre-history.

This means even isolated extremist claims hit a raw nerve, reinforcing the narrative that Cyprus is perpetually vulnerable to outsiders trying to turn it into ‘their’ land.

Stefanos Stefanou, leader of the opposition AKEL party, sounded the alarm: “If we don’t take effective action now, one day we’ll find that this country is no longer ours” (ynetnews.com).

Such language carries historical weight. For a people who lost half their country in 1974, the prospect of losing more land, this time through purchase rather than tanks, is terrifying. Stefanou, warned that the growing pattern of land acquisitions by Israelis near strategic sites, along with the development of gated communities, Zionist schools, and synagogues, poses a serious national sovereignty threat. He even stated: “If we don’t take effective action now, one day we’ll find that this country is no longer ours.” Daily Sabah+15ynetnews+15Mizan Online+15

These sentiments were echoed in multiple outlets, AKEL framing the trend not as xenophobia, but as concern over long-term land control. Lemkin Institute

National news media, including Cyprus Mail, Politis, and others, have documented the acquisition of nearly 4,000 Israeli-linked properties since 2021, many in Larnaca, Limassol, and Paphos, often next to ports and military sites. Lemkin Institute

Critics warn that these developments resemble a ‘silent occupation’ and may pave the way for limited-access zones and erosion of local land rights. Al Mayadeen English Mizan Online

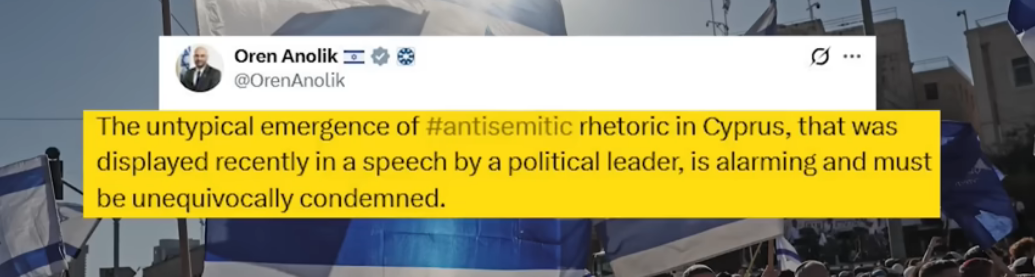

The Israeli ambassador to Cyprus, Oren Anolik, has hit back hard. He accuses Cypriot politicians of indulging in antisemitic tropes and insists this is ‘private market activity’ with no connection to Israeli state policy PressTV.

The Cypriot imagination does not easily separate private buyers from broader geopolitical patterns. The optics alone, gated compounds, biblical language, foreign wealth changing local demographics, are enough to spark fears Almayadeen.

It is not lost on the Cypriots that the Zionist settlements in Palestine were private land acquisitions from absentee landlords in Beirut and Damascus.

In response, AKEL defended its stance as grounded in issues of land control and economic access, not ethnic or religious bias. Lemkin Institute

For Israelis, Cyprus may simply be a convenient escape valve, a place to buy a villa, secure an EU foothold, or raise children away from the turmoil of the Middle East. For Cypriots, it looks different. It looks like another chapter in a long history of being colonised, divided and displaced.

To a certain point, the Israeli ambassador is right to warn against antisemitic rhetoric, although it must be stated that it is the default of Israelis to denounce any criticism, however justified, of the actions of Israelis as antisemitic. It should also be noted that Cyprus has a long and positive Jewish history and Cypriots are not by culture or definition, antisemitic. To dismiss Cypriot fears outright is to ignore the context in which they arise. On an island where the north is still occupied, the south still hosts colonial bases, and the people still live with the legacy of imperial betrayal, the suspicion of foreign encroachment is not irrational. It is woven into Cypriot history.

Cyprus has always been small, and others have always been big. The Ottomans, the British, the Turks, the Israelis: each has left their mark on its land. In 2025, as Israeli gated compounds rise along the southern coast and property prices soar beyond local reach, Cypriots cannot fail to see parallels with the West Bank and are once again asking the same old question: when will this island finally be ours?

So what alarms Cypriots is not simply the numbers. It is the form these acquisitions are taking: gated enclaves, whole complexes bought up by Israeli companies, private schools and synagogues being established. To critics, this feels uncomfortably like the architecture of West Bank settlement transplanted into Cypriot soil. They look suspiciously like West Bank settlements.

For Greek Cypriots, this is not ancient history. It is an open wound. Families still keep the keys to houses they cannot return to. Towns remain divided by barbed wire. The trauma of dispossession is passed down through generations.

When Cypriots hear talk of ‘settlements’ in the south, even if they are made through market transactions, not military force the association is instant. What happened in the north, they fear, could happen again.

We cannot ignore the elephant in the room. Israel stands accused of genocide and is facing proceedings for war crimes at the International Court of Justice. In this climate, Cyprus cannot afford to be seen as complicit, even indirectly. Its geography places it uncomfortably close to the conflict zone, and its EU membership means its actions are under scrutiny from both Brussels and the wider international community. If Cypriot ports, airspace or financial systems are in any way used to facilitate Israel’s military machine, Nicosia risks reputational and even legal consequences. This explains the country’s caution: Cyprus knows that any hint of association with a state under investigation for the most serious crimes in international law could undermine its diplomatic standing, damage its credibility, and drag it into the dock by proxy.

Another layer of unease stems from the influx of wealthy Israelis spearheading land acquisition on the island. It is not unreasonable to assume that those with the resources to buy up swathes of Cypriot property are deeply connected to Israeli financial and political networks. Some, though certainly not all, may therefore be complicit, directly or indirectly, in sustaining or benefiting from the apparatus currently prosecuting the war in Gaza. This creates a moral and political dilemma: Cyprus risks becoming a safe haven for capital that is, at the very least, ethically stained by association with war crimes. For an EU member state, this is not simply a matter of real estate speculation; it is a question of whether Cyprus is willing to allow its soil to become an offshore extension of a state under international indictment.

In this context the current Israeli property boom is not an isolated development. It is simply the latest in a long continuum of uncomfortable settler colonialism.

- The Ottomans ruled Cyprus until 1878.

- The British annexed it, ran it as a colony, and kept bases after “independence.”

- The Turks invaded and occupied the north.

- Now Israelis are buying up the south.

Each episode is different in form, imperial conquest, colonial enclaves, invasion, investment: but the underlying theme is the same, outsiders reshaping the island for their own purposes, while Cypriots are pushed aside.

This is why the rhetoric is so heated, why words like ‘silent occupation’ or ‘settlements in all but name’ resonate. Cypriots see a pattern: whenever foreigners move in, it is Cypriots who lose.

A bit of shameless self-plugging here. This is www.TetleysTLDR.com blog. It's not monetised. Please feel free to go and look at the previous blogs on the website and if you like them, please feel free to share them.