We need to talk about Richard Medhurst

TetleysTLDR: The summary (150 words)

Journalist Richard Medhurst has been fully exonerated after more than a year under terrorism investigation, with no charges, no trial and no evidence ever produced. Arrested under Section 12 of the Terrorism Act 2000 for journalism on the Middle East, his case exposes how counter-terror law is increasingly used as lawfare. The arrest, seizure of devices and prolonged bail amounted to a serious interference with freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Strasbourg case law, notably Dink v Turkey, makes clear that states have a positive obligation to protect journalists from legal harassment and chilling effects, not to generate them. Section 12’s vague criminalisation of ‘expressions of support’, absent intent or material assistance, fails basic tests of legality, necessity and proportionality. Medhurst’s exoneration does not show a system working; it shows a state willing to damage journalists first and justify itself later.

TetleysTLDR: The article

Richard Medhurst’s Exoneration Shows How Terror Laws Are Being Used to Break Journalists, Not Protect the Public

Richard Medhurst has been exonerated. That is the official phrase. What it means, stripped of bureaucratic varnish, is that the British state spent more than a year treating a journalist as a terrorism suspect and then walked away empty-handed. No charges. No trial. No evidence. Just silence, as if the preceding months of disruption, intimidation and reputational damage were an administrative footnote rather than the point of the exercise. The Crown Prosecution Service has dropped the case. Bail has been lifted. Medhurst is free to resume his work but to describe this as the system correcting itself is to fundamentally misunderstand what has taken place. (The Canary, 2025)

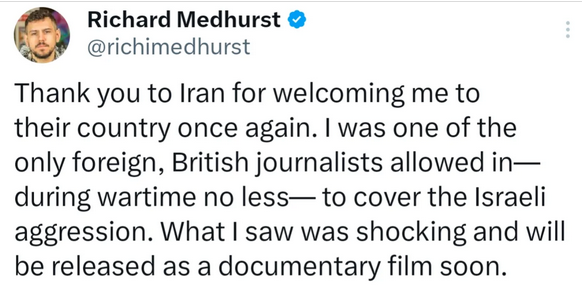

Medhurst was arrested under Section 12 of the Terrorism Act 2000, which criminalises expressions deemed supportive of a proscribed organisation. His alleged offence was not violence, recruitment or material assistance.

It was journalism: commentary and analysis on the Middle East and Western foreign policy. That alone should have raised alarms. Instead, it triggered a year-long exercise in state overreach. Under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, freedom of expression includes the right to impart and receive information without interference by public authority. Restrictions are permitted only if they are lawful, necessary and proportionate in a democratic society. These are not optional guidelines. They are binding legal standards.

Now in the interests of balance I'd like to declare that I don't share some of Richard's views. I believe he's wrong bang on the button about Israel but wrong on Ukraine, he's certainly further to the left than I am. That said as a journalist he should be allowed unmolested to share those views and report things as he see them and equally be challenged on them in open forum. What shouldn't happen is that he should be arrested for them and retrospectively charged for them under terrorist legislation. This is raw unadulterated lawfare and its about the state shutting up voices that make it uncomfortable.

Measured against them, Medhurst’s treatment looks indefensible. Arresting a journalist for his reporting is an interference with Article 10 in its purest form. Seizing his devices compounds that interference by endangering source confidentiality, which the European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly identified as a cornerstone of press freedom. Prolonged bail and legal limbo deepen the harm. The fact that no prosecution followed does not neutralise the violation.

In human rights law, the damage is often done long before a case reaches court. That principle was made explicit in Dink v Turkey (2010), where the Strasbourg court held that the misuse of criminal law against a journalist, even without conviction, can create a chilling effect incompatible with Article 10. Crucially, the Court emphasised that states have a positive obligation to protect journalists from intimidation and legal harassment, not to subject them to it.

That obligation was not merely neglected in Medhurst’s case. It was inverted. This is not an isolated episode. A pattern has emerged in which journalists, activists and protesters are arrested under counter-terror legislation, subjected to intrusive investigations and prolonged uncertainty, and then quietly released when evidence fails to appear: Arrest first. Disruption second. Collapse last.

The absence of accountability when these cases disintegrate is not a bug; it is a feature. Section 12 sits at the heart of the problem. Unlike most serious criminal offences, it does not require proof of intent or material support. It turns instead on whether speech could be interpreted as supportive or recklessly encouraging. This vagueness is not incidental. It collapses the distinction between explanation and endorsement, between reporting and advocacy. It allows context to be reclassified as complicity.

From a human rights perspective, this raises acute issues of legal certainty. Article 10 requires that individuals be able to foresee, to a reasonable degree, the consequences of their actions. When journalism on controversial subjects can be retrospectively reframed as terrorism then that requirement collapses entirely.

Press freedom organisations warned of this danger from the outset. The National Union of Journalists and the International Federation of Journalists condemned Medhurst’s arrest, warning that the use of terrorism legislation against journalists would have a chilling effect far beyond the individual concerned. NUJ & IFJ Statement

Strasbourg jurisprudence backs them up. The European Court has repeatedly stressed that measures which deter journalists from contributing to debate on matters of public interest strike at the heart of democratic society. Political speech and reporting on foreign policy attract the highest level of protection under Article 10, not the lowest. Medhurst’s work focused on the Middle East, an area where criticism of state violence and Western complicity is increasingly treated not as legitimate dissent but as a security concern. Independent reporting has documented how counter-terror powers are disproportionately deployed against journalists and activists critical of UK or Israeli policy, with investigations frequently collapsing once scrutiny intensifies. Declassified UK

The uncomfortable truth is that exoneration does not repair the damage. There is no automatic review of whether the initial interference met the tests of legality, necessity and proportionality. There is no remedy for the months of disruption. The state pays no price for getting it wrong. The journalist absorbs the cost.

This is why Medhurst’s case matters. Not because it is exceptional, but because it is becoming typical. It shows how counter-terror law now functions as a tool of pre-emptive discipline rather than last-resort protection. The Terrorism Act 2000 was forged in a different political era and expanded with little regard for long-term consequences. Section 12, in particular, now sits in open conflict with the UK’s obligations under Article 10 as interpreted by the European Court of Human Rights.

Richard Medhurst can move on. The law that ensnared him remains fully operational.

If Britain is serious about press freedom and human rights, it cannot continue to treat journalists as acceptable collateral damage in the pursuit of narrative control. Dink v Turkey made clear that democracies have a duty to protect journalists from the chilling effect of the law. Medhurst’s exoneration shows how far the UK has drifted from that standard — and how normalised that drift has become.

Tetley is a left of centre writer and retired musician based in the UK. A former member of the Labour Party, he writes political analysis exposing Britain’s authoritarian drift, the criminalisation of protest, and the erosion of civil liberties.

A bit of shameless self-plugging here. This is www.TetleysTLDR.com blog. It's not monetised. Please feel free to go and look at the previous blogs on the website and if you like them, please feel free to share them.