Yr Hen Ogledd: the erased history of the North

TetleysTLDR: The summary

TetleysTLDR: the Long bit

Let’s start with the basics: from the Pennines to the Solway, from Yorkshire to Strathclyde, people spoke Cumbric well into the early medieval period. This isn’t radical revisionism; it’s the standard scholarly position. Archaeology shows continuity between late Roman and early medieval populations (Higham, 1992). Linguistics shows Cumbric persisting centuries after the Anglo-Saxon takeover (Jackson, 1953). Genetics shows that modern Northerners share deep pre-Saxon roots with Wales (Oppenheimer, 2006; Schiffels et al., 2016). In other words: the Celtic North - Yr Hen Ogledd didn't vanish and it was never replaced.

It just learned a new language under new bosses. The idea of mass Anglo-Saxon displacement: the neat Victorian myth of 'Germanic settlers sweeping aside the Celts' has been dismantled by decades of scholarship (Pryor, 2004; Hills, 2009). The land didn’t change its people.

The people changed their rulers and the fingerprints of that earlier world are still everywhere.

- Rivers especially hold the memory. Hydronyms are incredibly instructive.

Derwent (from derw, ‘oak’).

Don (from Dôn, a Celtic mother-goddess).

Tyne may come from a Brythonic root meaning ‘river’.

Ure, Aire, Humber, Wharfe, Esk, Wear and Tees all have pre-English origins. - Hills and valleys similarly expose the substrate.

Pen- in Penrith, Penyghent, Pendle all from pen, ‘hill’ or ‘head’.

Blencathra preserves blain (‘top’) and cathrach (‘chair/fort’). - Even cities: Carlisle is from Caer Luel (‘the fort of Luel’); Leeds was Loidis, a Brythonic district; York was Eboracum, from ebor (‘yew tree’).

Pen-y-ghent, Blencathra and the Brythonic North beneath the hills

If rivers whisper Brythonic, the hills bloody well shout it. Look at the Pennines: our great spine of the North, and a 300-mile monument to Celtic memory.

- Pen-y-ghent from pen (‘hill’) + gynt (‘winds’).

- Pendle pen + hyll, a linguistic hybrid: ‘hill-hill’ in Celtic and Old English.

- Penrith ‘red hill’.

- Blencathra from blain (‘summit’) + cathrach (‘fort’), the “chair-shaped hill”.

- Cumbria from Cymry, meaning ‘the fellow countrymen’, the same word modern Welsh use to describe themselves.

Brythonic people named the land because they were custodians of the land for future generations. These names are artefacts but they are also acts of resistance, the lingering graffiti of a culture that refused to vanish. Even the word cumb (‘valley’), which survives as coomb in dozens of Northern place names, comes from the Brythonic cwm, still used in modern Welsh. When you hike the Lakes or the Dales, you’re quite literally walking through Welsh-named country.

Craven

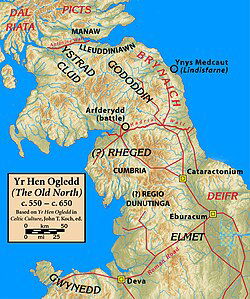

Craven sits awkwardly in the historiography because it never appears in the chronicles as a named kingdom, but everything we know about the region points to it functioning as a semi-autonomous Brythonic territory, culturally and politically distinct from its larger neighbours. Archaeological continuity from the late Roman period, concentrated around places like Skipton, Malham and Giggleswick, shows an enduring local elite rather than population replacement (Higham, 1992). The very name ‘Craven’ is certainly Brythonic, from craobhan (‘rocky place’), perfectly describing the limestone scars and high fells (Koch, 2006). Its location between Rheged to the northwest and Elmet to the southeast suggests it operated as a buffer zone, a borderland Brythonic community maintaining its identity while larger kingdoms clashed around it. When Northumbria expanded westward in the 7th century, Craven was one of the last upland regions brought under Anglo-Saxon rule, implying a local leadership strong enough to resist assimilation. In other words: Craven may not have been a 'kingdom' with a name in the chronicles, but it was certainly a Brythonic force with its independence written into the landscape and preserved in the stubborn Brythonic place-names that still cling to its hills.

Gododdin:

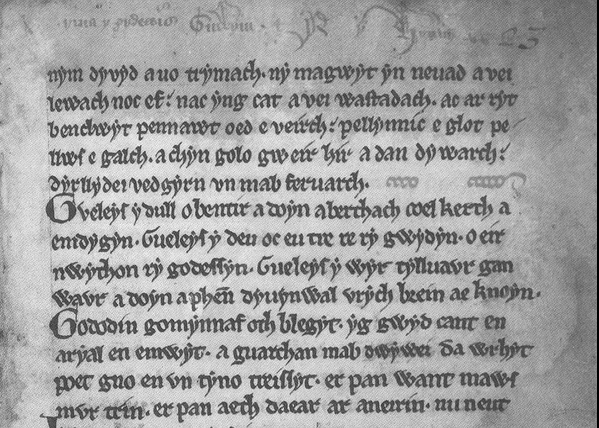

The Kingdom of Gododdin was one of the most formidable Brythonic realms of the Old North, stretching from the Lammermuir Hills to the Firth of Forth and centred on Din Eidyn (modern Edinburgh) long before the Scots or the English laid claim to it. Emerging from the earlier Roman-era Votadini, the Gododdin were a warrior aristocracy who held the eastern marches against Anglo-Saxon Bernicia for generations. Their territory formed a crucial northern bulwark of Brythonic power: upland, fortified, and fiercely independent. What makes the Gododdin so culturally important is not just their military role, but the fact that their poetic tradition survived the fall of their kingdom, carried south into Wales by exiled bards like Aneirin, whose epic elegy Y Gododdin immortalised the warriors who died at Catraeth (Catterick). This means that the kingdom’s memory isn’t archaeological dust, it lives on in the earliest heroic literature of Britain. The Gododdin were not peripheral; they were a lynchpin of the Brythonic world, a northern stronghold whose fall marked the beginning of the end for the Old North.

Long before Northumbria claimed the North East, the region was a mosaic of Brythonic kingdoms and tribal polities that formed the eastern edge of yr Hen Ogledd. The most powerful of these were the Votadini, the Brittonic people whose lands straddled what is now south-east Scotland and Northumberland. Their southern territories around the Tweed, the Cheviots, the Northumberland Coastal Plain, and as far down as the Tyne and were firmly Celtic-speaking for centuries after the Romans withdrew. To the west lay the Brigantes, Britain’s largest Celtic confederation, whose influence spread across County Durham and into Teesside. These Brythonic communities weren’t passive victims of Anglo-Saxon expansion, they resisted fiercely, and their culture persisted long after Bernician kings like Ida and Æthelfrith pushed eastward. Place names across Northumberland and Durham river-names like Tyne, Wear, and Tees, and hill-names with Celtic roots prove a simple truth: the North East didn’t begin with the Angles. It was a Brythonic heartland, its kingdoms forming the final frontier of the Old North.

Sheep Counting: The language that stuck in the fields

If you want the single strangest, most beautiful survival of Brythonic in the North, you won’t find it in manuscripts or archaeological digs. You’ll find it in sheep fields. in counting chants: yan, tan, tethera, methera, pimp…This system known as yan-tan-tethera is found across:

- Cumbria

- Yorkshire

- Lancashire

- Derbyshire

- Even Northumberland and Durham in fragments

Compare it to Welsh:

- Welsh: un, dau, tri, pedwar, pump

- Northern: yan, tan, tethera, methera, pimp

This isn’t coincidence. It’s linguistic fossilisation fragments of Cumbric, the Brythonic language once spoken across the North, preserved by shepherds who had no reason to change the rhymes their grandfathers had used. As linguist Graham Isaac has noted, these counting systems form a 'living museum of Brythonic numerals' (Isaac, 2001).The land forgot. The scholars forgot. But the sheep didn’t.

Ancestry: The Paleo-Welsh North

Genetics backs this up: people in Cumbria, Lancashire, Yorkshire and the North East share deep pre-Anglo-Saxon continuity with populations of Wales and the South West. The idea that the Anglo-Saxons ‘replaced’ the Britons is Victorian nonsense, the people remained largely the same; the ruling class and the language shifted. Culturally and genetically, Northern English people are, in many ways, Welsh people whose language was changed by force, politics, and time. One of the strongest proofs that the North of England was once deeply, stubbornly Brythonic lies in Welsh tradition. One such evidence is in The Mabinogion, a medieval collection of Welsh prose tales and heroic narratives, compiled from older oral traditions and manuscripts like the White Book of Rhydderch and the Red Book of Hergest, preserving some of the oldest surviving stories in the Brythonic world.- The landmark People of the British Isles (PoBI) project, published 2015 in created a 'fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles'. It shows that there are distinct genetic clusters in the UK, reflecting long-term regional continuity.

- According to that work, many people in the North of England (including Cumbria) cluster together genetically distinct from southern and eastern England.

- Some more region-focused commentary (e.g. on Cumbria) argues that Cumbria has 'among the most genetically and culturally distinctive' populations in Britain, suggesting strong survival of older (pre-Saxon/Brythonic) ancestry there.

Penrith, identified as the town in England showing the least evidence of Anglo-Saxon genetic assimilation

So Was the Culture Stolen?

I can imagine the answer to this in the style of on of those epic BBC documentaries with Simon Schama as he wobbles his head and spurts indignantly: "Well yes, actually! and the theft was three-fold".

1. Political Erasure

Northumbria absorbed Rheged and Elmet, then rewrote the region’s identity in its own image. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History barely acknowledges the Brythonic kingdoms except as obstacles to Christianisation (Bede, 731). A conquered people’s history became an inconvenience.

2. Linguistic Overwriting

English was imposed through:

- Administrative dominance

- Church structures

- Aristocratic language

- Trade networks

Cumbric didn’t die overnight, it probably survived into the 12th century (Jackson, 1953). But it was pushed out, marginalised until only sheep-counting rhymes remained.

3. Victorian Myth-Making

The Victorians are the real villains here. They constructed a triumphalist story of Anglo-Saxon England as the cradle of democracy, liberty and civilisation (Green, 1882). That narrative needed a clean break between 'Germanic England' and 'Celtic otherness'. So the North’s Brythonic past was:

- Downplayed

- Misrepresented

- Absorbed into an Anglo-centric national story

The modern English identity was built by erasing the parts that didn’t fit.

- The population of Northern England is overwhelmingly pre-Anglo-Saxon in origin.

- Anglo-Saxon migration contributed only a modest percentage of ancestry.

- The closest genetic relatives of many Northerners are modern Welsh and Cornish populations.

This isn’t fringe science it is the consensus view. What this means is simple: Northern English people are largely the same people who lived here in late Roman and sub-Roman times. In other words they're Brythonic by blood, even if the English by language. The North didn’t become 'English', it became anglicised.

Pendragon Castle near Kirby Stephen is the perfect symbol of conquest layered over conquest, and assimilation erased from the historical canon. The 12th-century Norman fortress wasn’t some innocent outpost in the hills; it was built deliberately, strategically to dominate and overawe the surviving Brythonic communities of the Eden Valley, the Cwn Eiden, the people of Eden, heirs of the old kingdoms of Rheged and Strathclyde. The Normans called it Pendragon Castle, but it wasn't a new build, it was a take over - the older name, Castell Pen Draig ‘the Castle of the Dragon’s Head’ points to something far deeper. The site itself sits on the footprint of an earlier Brythonic stronghold, a sub-Roman or even late Iron Age hill fort woven into the same legendary landscape that fed the tales of Merlin, Uther, and the stories of the Mabinogion. The Normans came late to this part of England. Not under William but under William Rufus, it was the last part of what is now England to fall. They built over a Celtic fortress because that’s where power already was. The layers tell their own story: a Brythonic citadel linked to the mythic kings of the Old North, overwritten by a Norman keep trying to stamp authority on a land it never truly understood. Pendragon is not just a ruin, just like Newcastle built on Segedunum, York on Eboracum and Catterick on Cattraith, it’s a palimpsest of the North’s stolen past, its legends and memory stubbornly refusing to die under the stonework of its conquerors.

Here’s the thing about buried histories: they don’t stay buried forever. Right now, scholars, amateur historians, linguists and proud Northerners are rediscovering:

- The poetry of Urien Rheged

- The borders of Elmet

- The Brythonic roots of Northern English dialect

- The Celtic landscape beneath every footpath

- The genetic truth of Northern ancestry

- The material continuity between Roman Britain and the medieval North

This isn’t nostalgia. It’s reclamation. It’s the assertion that the North’s identity is older, deeper, and more complex than the neat English stories mis-taught in school. It’s the rediscovery that the North wasn’t built by invaders. The so called 'Celtic fringe' isn’t a fringe at all, it’s the foundation beneath half of England.

And history is a leveller.

The Brythonic North was never lost. It was never destroyed. It was never replaced by some Germanic reboot. It was buried. It was stolen and sometimes renamed, by Angles, by Saxons and by Danes but the history refused to die. Whitby, that quintessentially English town on the coast of Yorkshire was called that by the Danes, as it was the farm (bi) of a Dane called Hvitabyr - [Hvitabyr-bi] before that the Saxons of Northumbria called it Streoneshalh, which [Streons Nook]. Before that it was a Brythonic fort at the mouth of Esk [Usk] 'Caeraberusk'. The Esk runs at the bottom of the steep valley that heads into the sea and flows with its ongoing Brythonic identity that it never relinquished.

The land remembers. The rivers speak Welsh. The hills wear Celtic names. The sheep understand counting in Cumbric and the shepherds rhyme in a tongue that would have been understood by Urien. The DNA speaks louder than the textbooks and the people of the North, yr Hen Ogledd, whether they know it or not, and whether they like it or not, carry the cultural memory of Rheged and Elmet, Craven and Godoggin in their bones. Maybe it’s time we stopped pretending we’re just the descendants of Anglo-Saxon settlers and admitted the older, deeper truth: we are the Brythonic North. We were always here and we’re not going anywhere.

The Modern Politics of a stolen past: why far-right English nationalism is built on fantasy

This is where the buried history of the Brythonic North punches straight through the paper-thin toxic skin of modern English nationalism, because the far right’s whole shtick depends on a past that simply didn’t happen. Their banners, their St George’s crosses, their crusader cosplay and 'Anglo-Saxon blood and soil' fantasies all rest on the delusion that England was once some culturally pure, ethnically uniform fortress built by noble Germanic settlers defending the island from foreign contamination.

It’s telling, almost too telling, that the very word Welsh comes from the Old English weallas, meaning foreigners or outsiders. The Anglo-Saxons slapped that label on the Brythonic peoples not because the Celts were foreign, but because the Saxons were and they knew they had no right to the land. It’s the classic colonial trick: project your own otherness onto the people whose land you’re taking, brand the natives as the outsiders, then rewrite the story so you look like the rightful heirs. The same sleight-of-hand happens today wherever a conquering power wants to absolve itself: Palestine, Western Sahara, Tibet take your pick. It’s always the same script: invade, rename, claim divine right, and call the original inhabitants strangers in their own country. The Anglo-Saxons did it in the 6th century; modern states do it now. Same shit, different millennia.

Well quite frankly it’s bollocks. Worse, it’s imported nonsense: half-baked from Victorian racial purity mythology and reheated by modern grifters who wouldn’t know the true land they claim to be patriots of from a hole in the ground. The truth is that England, especially the North, was forged not by purity but by collision: Brythonic kingdoms, Roman legions, Norse settlers, Danish law, Norman aristocrats, Flemish migrants, Irish labourers, South Asian and Caribbean communities, even Welsh iron workers. The country these clowns claim to 'defend' has never been one thing. It has always been layered, hybrid, contradictory, multilingual and mixed. As noted earlier 'English' kingdoms themselves weren't the origin of our country. The were built on top of older Brythonic societies whose people didn’t vanish, they just learned a new language under new elites. Which means the far-right’s beloved Anglo-Saxon identity is, historically speaking the shallowest layer in the pile. Look at their icons. St George? a Middle Eastern soldier who never set foot in England. Their crosses? Adopted by the English monarchy centuries after the Norman Conquest and originating in Angevin French, their myths of noble Saxon freedom-fighters? written down by Bede to justify a political takeover. Crusaders? mainly French and Holy Roman Empire and even the English ones spoke Norman French, their medieval nationalism? invented largely by the Victorians to justify empire.

The tale of Lludd and Llefelys in the Mabinogion talks of a second plague, believed to the the invasion of the Anglo Saxons, depicted as a white dragon in a battle with the Welsh, depicted by Y draig Goch. The northern Gammon should read more, or even read something that doesn't rot their head like the Sun or the Mail

These people are not guardians of tradition, they’re the gullible victims lapping up a national fairytale constructed to prop up a ruling class. When they wave their flags in Northern towns: in Durham, Sunderland, Middlesbrough, Bradford, Leeds they’re doing it on land where the English identity they unquestionably worship arrived centuries after the people who are most likley their ancesters lived there on land where the rivers still whisper Welsh and where the hills still carry Brythonic names, where the DNA still connects directly to the Celtic-speaking Britain. A Britain their ideology denies.

The irony should burn them.

They aren’t defending 'their' heritage, they’re erasing their heritage. The heritage of the very people whose votes they’re begging for but this historical illiteracy isn’t a harmless mistake: it’s politically dangerous.

Far-right nationalism needs the myth of ancient ethnic purity to justify xenophobia today. It needs a fake sanitised past to support a cruel present. It needs to pretend that 'England' was always monocultural so it can argue that diversity is somehow a modern threat rather than the historical norm.

The truth is the exact opposite: plurality is the oldest thing about this island. The far right’s cultural appropriation of England is not only abhorrent, it’s a deliberate act of historical vandalism. If pricks like the Reform Councillors in Durham or Hartlepool or Redcar actually cared about the North’s real heritage, they’d be learning Cumbric numerals, reading Y Gododdin, defending the legacy of Rheged and Elmet and realising that the whitewashed England in their heads is a product of Victorian propaganda and modern Faragist bullshit. But of course that kind of honesty would destroy their whole project. Their nationalism requires amnesia. It collapses the moment the true history of these islands comes into focus. That’s why reclaiming the Brythonic North isn’t just antiquarianism, it’s political resistance. The more we remember who we really are, how we have always been diverse, the more their hateful paper-thin myths fall apart and that’s why the far right hates history done properly: because it exposes them not just as bigots, but as frauds. Their England is a costume - a cartoon, a marketing exercise for a movement that fears the complexity and the beauty of our real past.

The truth is simple and devastating for them: England was never pure. England was never singular and the North was never theirs. It was, and in many ways still is, Brythonic and no amount of flags, chants or manufactured nostalgia will ever change that.

Sources & Suggested Reading

Bede (731) Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

Breeze, A. (2002) ‘The Kingdom of Elmet’, Northern History.

Green, J. R. (1882) A Short History of the English People.

Higham, N. (1986) The Kingdom of Northumbria.

Higham, N. (1992) Rome, Britain and the Anglo-Saxons.

Hills, C. (2009) The Anglo-Saxons.

Isaac, G. (2001) ‘Cumbric: the Brittonic language of the North’, University of Wales.

Jackson, K. (1953) Language and History in Early Britain.

Jarman, A. (1988) The Heroic Age in Welsh Literature.

Koch, J. T. (2006) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia.

Leslie, S. et al. (2015) ‘The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population’, Nature.

Nicolaisen, W. F. H. (1976) Scottish Place-Names.

Oppenheimer, S. (2006) The Origins of the British.

Pryor, F. (2004) Britain BC.

Schiffels, S. et al. (2016) ‘Anglo-Saxon migration and admixture’, Nature Communications.

Tetley is a left of centre writer and retired musician based in the UK. A former member of the Labour Party, he writes political analysis exposing Britain’s authoritarian drift, the criminalisation of protest, and the erosion of civil liberties.

A bit of shameless self-plugging here. This is www.TetleysTLDR.com blog. It's not monetised. Please feel free to go and look at the previous blogs on the website and if you like them, please feel free to share them.